Tag: Rangers

A Land Rights News article.

The Utopia rangers have taken two interns under their wing, showing them firsthand how they look after country.

Bree Bannister and Amit Rotenberg are part of an Indigenous Desert Alliance program that places future land managers with ranger groups for hands-on experience.

For two weeks, Ms Bannister, from Broome, and Ms Rotenberg, from Melbourne, worked with the rangers around Arlparra, northeast of Mparntwe (Alice Springs). They learned not just fire skills but about the cultural heart of the job.

The rangers liked having the interns along.

“They like to go around with us, see the country, learn about bush medicine and fire,” ranger Paul Club said.

“We’ve been showing them waterholes, sacred sites, bush plums– all the things we look after.”

The rangers showed the interns different burning techniques.

“There was a beautiful moment where [traditional owner] Sam started lighting matches and then a couple of rangers followed him. Then Helen [Kunoth] brought me over and showed me her technique of getting a big stick, lighting that on fire, winking at me,” Ms Bannister said.

“It’s been incredible, the rangers have been so welcoming, so funny and so generous in sharing their knowledge. I’ve loved every second of it.”

The four-week program began with a week-long intensive induction process at the IDA Desert Hub in Perth, where the eight interns met staff and were prepared for the field-based elements of the program, including the cultural and ecological aspects of Indigenous land management.

The IDA then placed interns with member ranger groups across the desert for two weeks of on-country experience, before a final week of reflection and debriefing in Perth.

The program is about matching the right people with the right land management jobs when there are no local Aboriginal applicants.

“The internship was created in response to IDA members and desert ranger teams who wanted better support for bringing new people into the sector right way,” the IDA’s sector development manager, Zack Wundke said.

“This way, they can get hands-on experience, decide if it’s right for them, and, if it is, start building the relationships and skills they’ll need to succeed.”

Ms Bannister, a trained nurse from Broome, wanted to test whether she was ready for a career change.

“When this internship popped up, I thought what a great opportunity to give it a go and see if I’m good for it. The biggest lesson has been to step back, watch, listen and observe. Being able to do that trumps all your qualifications.”

Ms Rotenberg, from Melbourne, has a master’s degree in environmental management and would like to work with Indigenous knowledge.

“I’ve learned that ranger work isn’t just about burning or weed control, it’s about being on country, telling stories and passing on knowledge. The women here have been so generous with me, showing me bush medicine plants and telling me whose country we’re on. I didn’t expect them to be so open, so quickly.”

On one school trip, the women taught children plant names in Alyawarre while the men lit fires in the background.

“It was beautiful,” Ms Rotenberg said. “The kids were excited, and the ladies just looked in their element. Everyone was so into it and looked glowing and happy to be out of the classroom. It was really nice to watch.”

Utopia’s ranger facilitator, Paul Evans, compared the program with an apprenticeship. “It’s a deep, hands-on introduction. New coordinators and facilitators need time to build trust and respect with countrymen and women, that’s the foundation. Without it, people can come and go quickly, which can leave a long-term impact on the community.”

The program is part of building the steady leadership that helps rangers to take on more senior positions. “When facilitators stay for the long haul, they form strong relationships with rangers, share valuable skills, and help build the confidence needed for rangers to step up and take on those roles themselves,” says the Central Land Council’s Boyd Elston, who also chairs the Indigenous Desert Alliance.

A Land Rights News article

Few newly-elected Central Land Council delegates get through their first council meeting without a peek in the how-to-manual for being a council member.

Each table has copies of the illustrated booklet Governance at the Central Land Council and many members like to look them up when they have questions.

They usually have lots of them: ‘Why do we check if we have a quorum and what is a quorum anyway?’

‘How do I know if I’ve got a conflict of interest and what do I do about it?’

‘What is a proxy and why might I need one?’

The CLC’s good governance guide has all the answers because it is based on years of feedback from CLC members.

It has been around for almost two decades, but the third edition is the best one yet.

So good, in fact, that Helen Wilson from the Lajamanu-based Northern Tanami Rangers has asked to take copies back to her community.

“I would like to have a book like that for all the rangers,” she said. “So we can learn about governance too and about how the CLC works. There’s no big words in the book, so it’s all plain English. They broke it down so it’s good to read. I might read it to my kids and teach them.”

“I think this book is really good – what governance means to us. It will bring a lot of learning and teaching to the younger ones, like my age, and everyone else.”

The lead ranger has been thinking on and off about representing her community on the council someday, once she moves on from ranger work.

When she visited the Uluru–Kata Tjuta National Park on other business in April she attended parts of the CLC’s induction and governance training day and started to leaf through the guide.

“The writing is all right, not too long and not too short. The pictures in the book are of local people, so that’s good.”

Another fan of the guide is governance trainer Maggie Kavanagh who ran the council induction during the first meeting of the CLC’s 2025-28 council term.

Ms Kavanagh has followed the development of the guide for many years and believes the latest edition shows that the council is taking governance support seriously.

“It is comprehensive, user friendly, has great graphics and is a terrific hands-on resource for council members to learn about their job,” she said.

Read the digital copy of Governance at the Central Land Council

A Land Rights News article.

Combining Aboriginal ways of knowing with scientific monitoring of bilbies makes for better research.

Lajamanu traditional owners and rangers are helping a researcher find bilby tracks, identify their desert environments and threats and develop conservation strategies.

Dr Hayley Geyle relies on the lead ranger of the Central Land Council’s North Tanami Rangers, Helen Wilson, and her community to find the shy nocturnal creatures. Together, they learn more about the size of their families and develop strategies to protect bilbies from cats and foxes.

“My work would not have been possible without traditional owners and rangers. They’ve taught me so much about how to track animals across this landscape. They have deep knowledge of bilbies–where they live, how they behave and what’s putting them at risk,” she said.

Studying bilbies over the past four years with Yapa has helped the researcher from Territory Natural Resource Management and Charles Darwin University gain clearer and deeper knowledge.

“It’s given me a whole new understanding of how these animals might be interacting across the landscape,” Dr Geyle said.

“It’s been really great to learn from elders and rangers and to bring that knowledge into our science. It’s definitely led to much better outcomes.” For example when looking for bilby poo, also known as kuna or scats.

“A study we published together showed that we were able to find a lot more bilby scats when we based our surveys on local tracking knowledge, compared to standard scientific methods.”

Ms Wilson said the traditional owners are keen to be part of the research.

“The community come out with us when we do the surveys. They really like to learn. It creates excitement.”

She said Yapa liked working with Dr Geyle because she listens to them. “We make a good team.”

The two-way knowledge sharing gained national attention with Ms Wilson and Dr Geyle winning the 2024 Bush Heritage Australia ‘Right Way’ Science award at the Ecological Society Australia conference.

“I feel happy and pleased because I am doing my work for my people, the community and country,” said Ms Wilson.

Before colonisation, bilbies lived across most of Australia. Today, they’re found in less than a quarter of their former range, mainly because of feral predators and changes to how country is burned and looked after.

In July, North Tanami rangers Ms Wilson, Travis Penn and Kealyn Kelly and traditional owner Silas James took Dr Geyle to known bilby sites on the Northern Tanami Indigenous Protected Area to test a method for controlling foxes that doesn’t harm dingoes.

The team checked on spring-loaded baiting devices and the motion-sensor cameras they had deployed earlier to monitor how foxes, cats and other animals interacted with the devices. They also surveyed track plots and flew drones to look for signs of bilbies and other animals. The cameras confirmed what traditional owners already knew: foxes are very busy in the area.

The team tested the baiting devices with dried meat but without the poison capsule they can release when triggered by foxes.

It consulted elders throughout the process to ensure dingoes, which are sacred to the area, would not be harmed. The trap’s design included a special collar that stop dingoes from triggering the devices.

“Next, we’ll go through the footage with the rangers and traditional owners and have a yarn about whether this method is a good fit for the Northern Tanami,” said Dr Geyle.

The rangers showed how good they are at finding signs of bilbies from a moving car. Driving at 40 kilometres per hour they asked to pull over every time they spotted new burrows metres from the track. Ms Wilson collected bilby poo while Dr Geyle recorded the locations on her phone app.

The team expanded the search by scanning hard-to-reach areas with drones. Then the workers searched the ground where the drone footage showed signs of bilbies.

“There’s a few things I’ve learned, like recording the data on the iPad and the phone,” Mr Kelly said. “The cameras also, I’m trying to figure out how they work and everything, and trying to put them in spots where they can’t get destroyed by fire or some other animal.”

He said Yapa ways are front and centre of the work.

“Some parts where we do the surveys, some women or some men aren’t allowed to go on that site… so we just work as a team you know, try to divide the group and try to record as much data as we can.”

Dr Geyle said the work the team produced together was strong, both from a scientific point of view and from a cultural point of view. “It’s really helped us collect better data, by working with people who know the land the best and can guide us to areas where bilbies or foxes are likely to be,” she said.

“More than that, it reflects a whole different world view, one that is deeply connected to country and built on generations of lived experience. This perspective brings knowledge, values and ways of seeing that are just as important as the science. Without it, we’d be missing a big part of the picture.”

A Land Rights News article

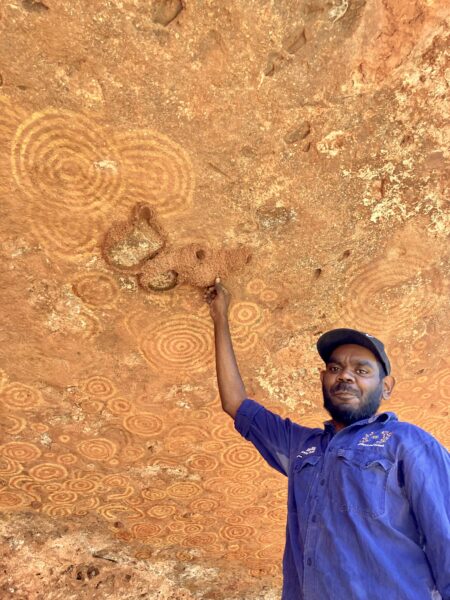

Since Ltyentye Apurte ranger Anton McMillan learnt how to remove swallow nests from rock art from the Kaltukatjara Rangers four years ago he has seized every opportunity to use his skills.

“The paintings tell our story. I want to share our knowledge,” he said.

He and his fellow rangers practiced the delicate craft of cleaning hornet wasp nests covering rock art on the Trephina Gorge cliff face.

Located near the creek bed, about a hundred metres from the carpark of the popular tourist spot, the once obscured painting is now clear for visitors to enjoy.

Mr McMillan uses the same technique for all nests made of mud, no matter whether they were built by birds or insects.

First he sprays turpentine on the nests to soften up the dirt on and around the paintings.

He carefully uses a hammer to remove larger chunks of the nest and chips at bits of dirt with chopsticks before removing leftover dirt with fine pointed picks.

He then reapplies the spray and waits for it to dry. “When the chemicals dry off is when you get to see where you want to start brushing away,” he said.

Protecting the art is painstaking work. “You don’t want to damage the painting.” Mr McMillan said it’s best to “slowly take your time”.

Visiting the site for the first time Ltyentye Apurte traditional owner, Jeremy Williams, was glad the rangers were restoring it.

“It is very important. It’s been there for years and years.”

The buzz the restoration is generating around his community motivates Mr McMillan to keep going.

He hopes the rangers will continue to care for the paintings. “They’ve been here for a long time, so hopefully they stay that way, and we keep looking after it.”

A Land Rights News article

When Tennant Creek locals rescued a bilby from its dead mother’s pouch in late 2021 it was the beginning of an amazing genetic journey.

After being told about a baby bilby whose mother had been killed on a road near Bootu Creek Mine Muru-Warinyi Ankkul ranger, Gladys Brown, travelled with family to rescue the hairless tiny creature.

Ms Brown, her niece Dianne Stokes and Ms Stokes’ daughter Amber drove two hours to retrieve the bilby from Ms Stokes’ son, Sebastian Waistcoat, who worked at the mine.

“It was a real family event. We all hadn’t seen a bilby before, we wanted to go and see what it looked like. First time looking at a small bilby. It’s a bit different to baby kangaroos. It had sharp nails,” she said.

“It was moving around probably missing its mother. I was cuddling it and making sure it was alright.”

Ms Brown named the joey Lukkanu, meaning star in Warlmanpa.

“I felt sorry for him losing his mother so I took him to the vet,” Ms Brown said.

After caring for him they gave Lukkanu to Tennant Creek wildlife carer Carol Hepburn who sought advice from the Alice Springs Desert Park and Sea World. She mothered, fed and provided him with round-the-clock care for a couple of months.

“I care for pretty much anything that’s not venomous, like wallabies, kangaroos and other smaller animals, ’’ Ms Hepburn said.

Once Lukkanu grew fur and became strong he was relocated to the Alice Springs Desert Park where his breeding journey began. Thanks to Ms Hepburn’s care during Lukkanu’s most vulnerable stages, he went on to greater bilby things.

As a wild-born animal he provided valuable genetic diversity for the Desert Park’s bilby breeding program and fathered two female and four male joeys.

Lukkanu’s male joeys Kulbar, Mr NT and Tyson were transferred to other captive breeding programs across the country. Kulbar was moved to Kanyana Wildlife in Western Australia, Mr NT to Charleville Wildlife Sanctuary in Queensland and Tyson stayed temporarily at Monarto Safari Park in South Australia and bred joeys Clive and Trish before moving to Currumbin in Queensland.

Early this year Ms Brown wanted to visit Lukkanu and found he had moved to Monarto Safari Park which hosts the Zoo and Aquarium Association’s national Bilby Species Management Program.

Lukkanu had been renamed TC but after Ms Brown let the park’s Bilby Metapopulation Coordinator, Claire Ford, know his Warlmanpa name they changed it back to Lukkanu.

In July Lukkanu met Gigi and they bred a new joey.

Now at the age of four (31 in bilby years) and weighing two kilos Lukkanu provides rare and valuable genetics to the intensive breeding program.

Genetic diversity is important to grow bilby numbers, prevent inbreeding and for overall healthier bilbies.

Introducing wild bilbies to breeding programs also helps bilbies to thrive out bush for generations to come. When bilbies are released back into the bush this genetic boost makes sure they have the best possible chance of survival.

“We can’t thank you enough… Lukkanu is making such a wonderful contribution to the bilby breeding program,” Ms Ford said.

A Land Rights News article

The Country Liberal Party government’s decision to break its $12 million Aboriginal ranger grant election promise is putting jobs, cultural knowledge and land management at risk across the Territory.

“The CLP is making a habit of betraying the trust of Aboriginal people,” CLC chair Warren Williams said.

“This is a slap in the face of the rangers who are out there managing country on the smell of an oily rag, protecting sacred sites and fighting fires, weeds and feral pests in some of the most remote areas of the Territory,” he said.

Former opposition spokesperson for Parks and Rangers Bill Yan, now the NT’s treasurer, said just before last year’s NT election that the CLP would continue Labor’s ranger grants.

He promised to deliver $3 million annually over four years to support Aboriginal rangers with critical training, equipment and infrastructure upgrades and job security – exactly as the previous Labor government had done for eight years.

Paddy O’Leary, the chief executive of Country Needs People, counted on him to keep his word.

“We were actually shocked that a government would so clearly promise, very directly, to fund a specific program unambiguously and without conditions, and then turn around in their first budget and break that promise,” Mr O’Leary said.

He said the backflip means rangers across the Territory won’t be able to afford the repairs, spray packs and protective equipment they need to do the job.

The CLC employs more than 90 rangers across 14 groups.

Mr Williams said their work “benefits all Territorians – from tackling feral pests to reducing carbon emissions – and the government’s broken promise puts this work and these jobs in jeopardy”.

Top End rangers are “outraged at this broken promise”, Northern Land Council chair Matthew Ryan said, adding that they were already significantly under-resourced to properly manage land and sea country.

“This government has revealed its plans to leave Aboriginal rangers behind,” he said.

Much of the Aboriginal ranger programs are funded by the federal government, but the ranger grants of the NT government have made the difference between groups limping along and thriving.

“Rangers will definitely scale back some of their activities, such as fighting weeds and tackling buffel grass, protection of sacred sites, which will mean fewer jobs on the ground,” said the CLC’s ranger program manager, Boyd Elston.

“Fewer opportunities for communities that really don’t have many other opportunities.”

“We were really shocked that the government would cut that kind of investment with so many positive outcomes. Kids want to be rangers and have the opportunities to move into those positions.”

NT environment minister Joshua Burgoyne said funding had been exhausted.

“Our government’s number one priority is law and order, including spending on frontline priorities such as police, courts and corrections.”

He said the CLP would “continue to work with Aboriginal ranger groups across the Territory to ensure we can support them in their important work moving forward”.

Mr Williams wants nothing less than a full reinstatement of the ranger grants.

“Your fine words before the election about supporting the bush ring hollow when you turn your backs on one of the proven success stories in remote community development as soon as the election is over,” he said.

“Our rangers and the country they care for deserve better. They will remember your backflip, as will voters.”

This is an article from Land Rights News July 2025. Read the full paper here.

A Land Rights News article

The Central Western Desert Indigenous Protected Area was a long time coming, calling for two days of celebrations.

During one of the hottest March weeks in living memory, hundreds of traditional owners and their supporters gathered at Ilpili, a significant water site in the middle of Australia’s newest IPA.

As their people had for tens of thousands of years, they came from all over the four million hectare area and beyond to perform ceremonies and introduce a new generation to their country.

They also signed an agreement with the Australian government to look after it for all Australians.

The two permanent springs seeping from Ilpili’s limestone make it an important gathering place.

The site lies between Walungurru (Kintore) and Watiyawanu (Mount Liebig), and is Papunya elder Karyn McDonald’s grandmother’s country.

“This is an important sacred place,” she said.

“Last night I was crying because I was remembering how my ancestors used to stay around this area. And it was really difficult, winter season and hot season, to look around for food. When I came here I felt my ancestors whispering to me. I felt my tears,” she said.

“We’re really proud to look after the country, the rock holes, water holes and all the animals, for the kids’ future. For them to learn from us so they can pass it on to the future generations,” Ms McDonald said.

She said feral camels pose the main threat to Ilpili’s springs.

“They just come, drink, have a bath. That’s how they are spoiling our water holes. The rock holes as well. We need to keep our country safe.”

Ms McDonald wants the Anangu Luritjiku and Walungurru ranger groups to “listen to the traditional owners” as they look after country between them, following an IPA management plan.

For the IPA management committee, getting rid of buffel grass and camels is of the utmost importance.

It’s the “main thing” for IPA committee member Patrick Collins, and why he signed up for the Australian Government funds that will flow with the IPA agreement.

“Water first, before we can come and look after country. Camels always smashing all the water. We need someone to help us. That’s why we’re trying to get someone to give us a little bit of money and work with us to look after the water and push all the camels to somewhere else.”

The celebration was the reward for all the work traditional owners and the Central Land Council started in 2017.

“We’re happy today,” Mr Collins, a CLC delegate from Watiyawanu, said after he signed the agreement.

“We’re trying to look after country. We travel around and see all the kids and get all the rangers to work with us to fix my country.”

School kids from his community spent the first morning of the gathering in the sand dunes north of Ilpili, learning how to track animals from kuyu pungu (master trackers) from Kiwirrkurra, Nyirrpi and Yuendumu.

“We want to learn the kids to carry on what we’re doing, so we’re passing story on to the kids and they can pass on the story when they grow up,” Mr Collins said.

“We’ve been learning with our grandmother and father how to catch kangaroo and goanna. We want to learn the kids to track animals, which way the animals are going, which way they are turning, see fresh tracks and old tracks. ‘Oh, we might follow fresh tracks’. So we are following the right track. ‘It must be here, where the fresh track is’.”

After a couple of hours of tracking in more than 40 degrees heat everyone retreated to whatever shade they could find.

Luritja interpreters helped the kids to relax with kuyu pungu Christine Michaels Ellis, her mum Alice Henwood and Enid Gallagher, who talked to them in Warlpiri.

“I was really happy with these kids,” Ms Michaels Ellis said.

“We asked them to recount. That’s what we always do with our rangers. They recounted back to us what they had seen today – snakes, camel tracks, fox tracks, sand goanna, scorpion burrows and centipedes, and old cat tracks as well. And they were really happy. It was really great.

“I told them tracking is really important so they can pass on the knowledge from the old people. Without the elders there will be no more tracking, so they have to pass knowledge to the young people.”

Students from across the IPA prepared for the big day by practising purlapa (ceremony) with the elders, and some carved and painted their own small digging sticks.

The rangers of tomorrow visited rock holes to learn from elders and scientists how to test the water quality and keep them clean.

“If they become a ranger they can learn their kids,” Ms Ellis Michaels said.

“If they haven’t got songlines they have to record it. That’s what Warlpiri people do at Yuendumu. They get records from the old people, and take it to PAW [Pintupi Warlpiri Anmatyerr Media], and they save it.”

With precious cultural knowledge and nine threatened animal species to protect on the IPA, the rangers have their work cut out.

Those who have to make it all happen feel up to the task.

“We’ve got the princess parrot, the (central) rock rats, and we’ve got the great desert skink in these areas, but there’s so many other more projects that we have planned,” the coordinator of the Papunya-based Anangu Luritjiku Rangers, Lynda Lechleitner, told the ABC.

“This IPA gives us our own voice and brings all the communities together in managing our land,” she beamed.

“It’s also going to make it faster to deliver our work on the ground because we are all working towards the same plan.”

The IPA program is an Australian government initiative that has helped Aboriginal people look after the unique natural and cultural values of their land since 1997.

Under the Central Western Desert IPA agreement the CLC will receive approximately $1.7 million for four years to help traditional owners and rangers to protect country and culture.

This is an article from Land Rights News July 2025. Read the full paper here.

The Central Land Council condemns the Northern Territory Government’s decision to backflip on its $12 million Aboriginal Ranger Grants election promise.

“The CLP has betrayed our trust and puts jobs, cultural knowledge and land management at risk,” CLC chair Warren Williams said.

Before the 2024 election, the Country Liberal Party promised to deliver $3 million annually over four years to support Aboriginal ranger groups with critical training, equipment and infrastructure – a commitment it has now scrapped in this week’s budget.

“This is a slap in the face to the rangers who are out there managing country on the smell of an oily rag, protecting sacred sites and fighting fires in some of the most remote areas of the Territory,” he said.

“Aboriginal ranger programs benefit all Territorians – from tackling feral pests to reducing carbon emissions – and the government’s broken promise puts this work and these jobs in jeopardy.”

The CLC supports 15 ranger groups across Central Australia, employing more than 90 Aboriginal rangers. The promised funding would have supported critical training, equipment upgrades and job security.

“This broken promise hits especially hard in communities where ranger jobs are among the few opportunities for meaningful, culturally appropriate work,” Mr Williams said.

“It undermines decades of investment in local efforts to look after country.”

Mr Williams called on the government to honour its promise and reinstate the grants in full.

“Your fine words before the election about supporting the bush ring hollow when you turn your backs on one of the proven success stories in remote community development as soon as the election is over,” he said.

“Our rangers and the country they care for, deserve better. They will remember your backflip, as will voters.”

Aboriginal rangers from the southern half of the Territory and beyond will blend traditional knowledge with the latest technology at this week’s annual Central Land Council ranger camp at Ross River.

This year, rangers will split into gender groups as they learn to fly drones to capture images of sites and landscapes for their monitoring programs.

The accredited training includes night-time demonstrations of infrared drone sensor technology which can capture 3D footage and conduct surveys both day and night.

The rangers will also practice using software to manage data from plant and animal surveys, produce maps of country for conservation and cultural significance and use digital mapping to virtually bring traditional owners out onto country.

Warlpiri ranger Travis Penn, from Yuendumu, looks forward to building on his experience using Google Earth Pro and other programs to produce maps of country.

“It will be good to use this new technology to show elders the work we’re doing on their country. We need more practice in our region, and I hope we can do more of that this year,” he said.

For the first time, female rangers will train in women-only groups to ensure they all gain hands-on experience with digital tools.

“This ‘by women, for women’ training empowers female rangers to develop their skills in a supportive environment,” CLC general manager Mischa Cartwright said.

The rangers will learn how to collect, analyse and share land management data with the technology.

They will install and use sensor cameras to photograph threatened animals and their predators, digitally map populations and distribution areas and conduct site surveys sites with drones.

The training sessions will blend traditional land management skills, such as cool season burning and animal tracking, with western fire and feral animal management techniques.

The rangers will practice how to bait and trap feral cats and foxes.

First aid, snake handling, 4WD operation and the use of weed killing chemicals will also be covered.

The camp, from Tuesday 25 March until Thursday 27 March at the Ross River Resort east of Alice Springs, is the CLC’s main professional development event for its 14 ranger groups.

Rangers from the NT Parks and Wildlife Service, the Newhaven wildlife sanctuary and the Ngaanyatjarra Council are also attending.

On the Tuesday the Batchelor Institute will celebrate rangers graduating with conservation and land management certificates.

Anangu traditional owners are gathering at Ilpili, a significant water site between Walungurru (Kintore) and Papunya, to celebrate the new Central Western Desert Indigenous Protected Area on Wednesday, 12 March.

The IPA covers the Haasts Bluff Aboriginal Land Trust, some almost 40,000 square kilometres, and comes with additional resources allowing traditional owners and Central Land Council rangers to better care for country.

The IPA is the missing piece of the puzzle between the CLC-managed Southern Tanami, Northern Tanami, Angas Downs and Katiti Peterman IPAs, adding to a network of conservation areas larger than Victoria.

It forms part of a 435,000 square kilometre cross-border protected desert area that also includes neighbouring Uluru-Kata Tjuta and Watarrka national parks.

The IPA features rich cultural landscapes that are home to rare and endangered native plants and animals.

Over the past two decades, nine threatened species have been found here, including the critically endangered central rock rat that survives in the ranges around Papunya.

“The Central Western Desert IPA is not just about conservation,” CLC chief executive Les Turner said.

“It is also about empowering traditional owners to drive the development of the region by creating good jobs on country.”

The IPA’s traditional owners are looking forward to protecting it against feral camels, buffel grass, wildfires and other threats with the help of federal government funding.

The CLC’s Anangu Luritjiku and Walungurru ranger groups will manage this land under the guidance of the traditional owners, following a detailed IPA management plan.

“This IPA gives us our own voice and brings all the communities together in managing our land,” Anangu Luritjiku ranger group coordinator Lynda Lechleitner said.

“It’s also going to make it faster to deliver our work on the ground because we are all working towards the same plan.”

The rangers of tomorrow will be front and centre of the community celebration at Ilpili, 400 kilometres west of Alice Springs.

Children from schools across the land trust will join the adults for purlapa (ceremonial dancing), billy can races, spear throwing, sand painting, water testing and animal tracking.

The Australian Government’s $231.5 million IPA program supports this project.

IPAs are established under agreements between First Nations peoples and the Australian Government to manage and protect areas of land and sea for biodiversity conservation.

They make up more than 13 per cent of Australia’s landmass and more than half of the national reserve system.

The government has set a target to protect and conserve 30 per cent of Australia’s land and oceans by 2030.

The Central Western Desert IPA adds nearly four million hectares to help reach this target – more than 24 per cent of Australia’s landmass is now protected.

MEDIA CONTACT: Sophia Willcocks | 0488 984 885 | sophia.willcocks@clc.org.au

The Central Land Council will celebrate the opening of a new ranger hub in Kintore (Walungurru) on Wednesday, 12 February.

The Walungurru [wah-loo-NGOO-roo] Rangers, community residents, members of the Central Western Desert Indigenous Protected Area sub-committee and CLC staff will open the hub at 11am with a celebration including purlapa (ceremonial dancing) and ribbon-cutting, followed by a barbecue and cake.

The hub replaces the group’s modest operational base, a small green garden shed.

The facility has been purpose-built for the ranger program and will support CLC meetings. It includes a large shed and an office for up to 20 people, shade structures for outdoor meetings, an external toilet block and a barbecue area.

“This hub is a game changer for the Walungurru Rangers and the Kintore community,” said CLC chief executive Les Turner.

“From humble beginnings in a small garden shed to this customised ranger hub, it’s a testament to what can be achieved when communities, traditional owners and organisations work together. The rangers have earned this space through their hard work and dedication.”

Marlene Spencer is on the board of directors for Pintupi Homelands Health Service which supported the establishment of the ranger group.

“This new ranger office means rangers have a place for their equipment, their shovels, their swags. They now have a place to get ready for their bush trips.”

Formed in 2019 with a grant from the 10 Deserts project, the ranger group includes four women and one male ranger, with three more male rangers joining soon.

Walungurru ranger Camilla Young says her people have been looking after country for generations.

“We are just following our grandmother and grandfather’s footprints. My grandmother would take me out bush and teach me how to look after country.

“Now, with the ranger program, we can keep teaching young ones how to look after country. They can get a job as a ranger,” said Ms Young.

“We’ve been waiting a long time for this. Many, many years. We now have a washing machine, toilets, and a big place to sleep. Other ranger groups now have room to stay when they visit,” said ranger Michael Wheeler.

The hub allows the rangers to keep working with their colleagues from the Anangu Luritjiku Rangers from Papunya, the Katiti Petermann Indigenous Protected Area, the Warlpiri Rangers and the Kiwirrkurra Rangers from Western Australia.

MEDIA CONTACT: Hazel Volk | 0473 644 533| media@clc.org.au

Warlpiri woman Alice Henwood is an expert tracker from Nyirripi.(ABC Alice Springs: Victoria Ellis)

“Nyiya Nyampuju?” What is this?

The call rings out across the red clay and sand.

The voice belongs to Warlpiri woman Alice Henwood from Nyirripi, a small community about 400 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs.

“Nyiya Nyampuju?” she asks again.

The group of people, spread out like the tufts of spinifex across the land, slowly gather around to look at where she is pointing.

They are quiet.

Alice knows the answer to her question, but right now she is teaching.

Finally, someone speaks up.

“Wardilyka,” Bush turkey, he guesses correctly.

The questions continue.

“Ngana-kurlangu?” Whose is it? “Nyarrpara-purda?” Which direction?

A group of people are tested on their tracking knowledge.(ABC Alice Springs: Victoria Ellis)

Over and over she asks the group with each new set of tracks that are found.

There are many of the puluku, cow.

There’s also the ngaya, cat, the puwujuma, fox, the warnapari, dingo and excitingly, the endangered walpajirri, bilby.

Full story here: Warlpiri preserve language, culture through animal tracking program for next generation – ABC News

More than 100 Aboriginal rangers will meet at Tilmouth Well this week for the Central Land Council’s annual ranger camp.

The launch of a bilingual animal tracking training package combining traditional and modern teaching techniques is this year’s camp highlight.

The CLC developed Yitaki Maninjaku Ngurungka [pronounce YEE-tuh-key MA-nin-tja-koo NGOO-roon-kuh] (reading the country) to ensure future rangers maintain ancient tracking knowledge and skills.

The training package features tailored learning activities supported by resources in Warlpiri and English.

Kuyu pungu [pronounce KOO-yu POONG-u] (experienced trackers), knowledge holders, educators and language experts developed it with the CLC’s Warlpiri and North Tanami rangers and other staff during the past three years.

Fourteen CLC ranger groups will explore the resources for the first time at the ranger camp on Tuesday afternoon.

The resources are ready to be adapted for other language groups across Australia’s deserts.

Kuyu pungu Jerry Jangala’s teaching style – the Jangala Method – was vital to the Yitaki Maninjaku Ngurungka project.

The elder from Lajamanu likes to ask questions that encourage learners to “push deeper”, but “nati yirdi-manta” (does not give away the answer) too soon.

“We talk about asking questions [so learners] give the right answer [to] get the right words into their hearts and minds,” he said.

Elder Enid Gallagher has been part of the project from the start.

“We have worked together to develop new ways to use old methods like recount and repetition. We have seen that recycling these old ways is working,” she said.

“On a recent biodiversity survey the rangers responded really well and got really excited from learning in this way.”

The camp allows rangers from the CLC region and beyond to upskill, take part in training and network.

Rangers will learn how to operate skid steer and four-wheel drive vehicles, practice catching poisonous snakes and will take part in first aid and smartphone video training.

This year’s ranger camp will focus on the rangers’ health and wellbeing, with the Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance of the Northern Territory delivering a mental health and a culturally responsive trauma informed program.

Guest speaker Cissy Gore Birch, a Jaru and Kija woman with more than 20 years of experience in land management and community development will speak about her journey and carbon farming.

The ranger camp is the CLC’s main professional development event for the men and women who make up its 15 ranger groups.

Contact: Sophia Willcocks | 0488 984 885 | Ranger camp program available from media@clc.org.au

Jeffrey Curtis has been waiting a long time for a new ranger hub in Tennant Creek, but now it’s come — and he’s looking forward to seeing how it helps young people in the remote Northern Territory town.

The new Muru-warinyi Ankkul Ranger base, built by an Aboriginal-owned construction company, is bigger and airier than the last, with modern amenities.

The ranger group had previously been splitting their operations between two locations, but the upgraded single site replaces what was basically “a very old shed”, according to Mr Curtis.

“I’ve been waiting for a new one for a very, very long time, maybe 10 or 15 years,” he said.

“I’m very happy for this new ranger hub and I hope it can do better for the future for our young ones.”

Rangers as role models

Muru-warinyi Ankkul Rangers was established in 2003 and is one of the oldest Central Land Council ranger groups.

The rangers care for country by monitoring plants, animals and water, but they have also mentored Tennant Creek high school students; up until the work experience program was stopped due to COVID-19.

Ranger Kylie Sambo said she hoped to restart the program.

“It [learning about country] starts early. If they know it when they’re young, it’s easy for them when they are older to get back to their roots,” she said.

“This is just a fun way of trying to work with non-Indigenous people on country.”

Tennant Creek has long been facing problems of youth crime, but Ms Sambo knows first-hand the power of positive role models.

“When I was at school I would go on a lot of trips with Central Land Council and write up essays about what we were doing on country and that would give me credit with school,” she said.

“That helped me a lot with being on the streets and doing all of these things that are happening now.

“I watched them [rangers] as a kid first and then said to myself, ‘I’m gonna be a ranger some day’. And sure enough, I am.”

New hub cooler and closer

The new ranger shed has a large fan, lockers, a tool cage, welding benches and, outside, a pressure cleaner and wash bay, while the house on the property received a new kitchen, bathroom, furnishings, solar panels and air conditioning.

A new conference space and server room will allow the site to be used as a training facility, while space for heavy equipment storage means the site can be a central hub for other ranger teams from Arlparra, Lajamanu, Daguragu, and Ti Tree.

Ms Sambo said having a new truck and tractor stationed at the hub will also be a boon, as central regional rangers previously had to travel to Alice Springs to borrow big equipment.

“[The hub] can make a huge difference with the time the rangers spend on roads to get to places and then come back to do the job, and then get that equipment back to where it came from,” she said.

“That’s been one of the biggest problems.”

Modern way of caring for country

Ms Sambo said the new hub would help her work on country and learn about her culture.

“And I’m being paid to do that, which is very important, because with this society we live in, everything revolves around having funding, having money to do so,” she said.

“The ranger program that’s in place allows us to tackle jobs given to us by traditional owners and that is also deeply important to us, because we are connected to the country.

“This is just a modern way of taking care of country and taking care of family and taking care of the plants and animals.”

Mr Curtis said the rangers made him proud.

“[I’m] very happy with my group. We were established from 2003, but we’re still going,” he said.

“This ranger group has achieved a lot — a lot of training has been done and a lot of land management and conservation … it’s made us a stronger group.”

An ABC news story posted 20 Feb 2024

The Central Land Council will celebrate the opening of the long-awaited Tennant Creek Ranger Hub at 37 Brown Street, Tennant Creek, on Wednesday, 14th February.

CLC chair Matthew Palmer, executive member Sandra Morrison and the traditional owner ranger advisory committee of the Muru-warinyi Ankkul Rangers will open the new ranger hub at 11am, followed by a celebratory barbeque and cake. The hub replaces the ranger group’s old operational base, a humble, dusty shed with only basic amenities.

The group had to split their operations between two locations, using the CLC’s Paterson St office for administration and training and the shed for works and storage.

The new facility offers modern amenities and ample space for the team to grow and professionalise. In addition to being a training facility, the ranger base will also house heavy equipment that other regional groups can use, making it a significant central ranger hub.

The hub is strategically located to offer ranger teams in Arlparra, Lajamanu, Daguragu, and Ti Tree space for training, for which they have had to travel to Alice Springs until now.

CLC chief executive Les Turner said the new facility does justice to the rangers’ efforts. “Twenty years after the rangers first started to look after country around Tennant Creek they now have a building that meets their needs and can grow with them as they continue to go from strength to strength.

They deserve no less.” When the CLC acquired the Brown Street lot in December 2022, it already had an office, a sizable shed and a three-bedroom house.

Following extensive collaboration with the rangers, it awarded a renovation contract to Aboriginal-owned business Dynamic Solutions. Work started last August and the contractor completed the renovation four months later.

The office underwent substantial improvements, including new power and data points for future growth, air conditioning, an updated layout that includes a conference space and a new server room and laundry area.

Ranger Jeffrey Curtis said the aircon provides welcome relief when temperatures are in the 40s week after week.

“It was very hard working in the old shed during the hot weather. Now we’re working in luxury in the cool shed.

Everybody is very happy to have a new work place and we’ve got to look after it.”

The shed upgrade features a large fan, lockers, tool cage, welding benches, and outside a pressure cleaner and wash bay.

These improvements help the rangers to keep equipment organised, ready to carry out their duties efficiently.

The house on the property received a new kitchen, bathroom and furnishings, ready to welcome visiting staff and trainers.

The solar panels make the hub more sustainable, as do water tanks and insulation. A new truck and tractor, to be funded by the Northern Territory Government Aboriginal Ranger Grants Program will soon be stationed at the hub.

Contact: Sophia Willcocks | 0488 984 885 | media@clc.org.au

Download PDF

The Central Land Council’s ranger camp will answer questions of Aboriginal rangers from Central Australia and beyond about the voice referendum.

A discussion about the referendum about the voice to parliament will kick off the week-long professional development and networking event on Monday, 20 March, at Ross River near Alice Springs.

Dr. Josie Douglas, executive manager policy and governance at the CLC and a member of the national referendum engagement group, and Jade Ritchie from the Yes23 campaign will present about the voice and answer the rangers’ questions.

They will be joined by Warumungu artist and CLC delegate from Tennant Creek, Jimmy Frank.

“Remote community residents have lots of questions about the referendum,” CLC chief executive Les Turner said.

“Our rangers want to know how the voice will help them to better look after country and improve the lives of their families.”

“I look forward to the discussions and hope it will inform the referendum campaign in remote communities,” said Mr Turner, who is also a member the referendum engagement group.

In line with the event’s peer-to-peer learning ethos, some rangers will learn to use their smartphones and tablets to produce short videos about what the voice means to them.

He said the location of this year’s CLC ranger camp, an hour’s drive east of Alice Springs, is highly symbolic.

“It’s where we held the Ross River Regional Dialogue in 2017, one of 13 such events across the country in the lead-up to the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

“Six years ago, at the same camp ground, more than 100 local Aboriginal people chose Central Australia’s delegates for the national constitutional convention at Uluru that called for voice, treaty and truth,” he said.

At this year’s camp around 140 rangers from 20 ranger groups from the southern half of the Northern Territory, as well as from South Australia and Western Australia, will also listen to each other’s voices.

The groups will give presentations about their work and hear from guest speakers such as Joe Morrison from the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation.

The camp features workshops and accredited training ranging from tracking animals to catching live venomous snakes, operating heavy machinery and burning country.

An awards ceremony with the Bachelor Institute for Indigenous Training and Education and NintiOne will celebrate the rangers’ education and training achievements.

More than a dozen rangers will receive certificates in conservation and land management.

Contact: Sophia Willcocks | 0488 984 885| media@clc.org.au

Download the PDF

An exciting new partnership in Central Australia between the traditional owners of the Ngalurrtju Aboriginal Land Trust, Central Land Council and Australian Wildlife Conservancy sees more than 300,000 hectares brought under conservation management

Alice Springs, NT, Thursday 12 May 2022 – The traditional owners, the Central Land Council (CLC) and Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) have signed an agreement to collaboratively promote the conservation of the unique cultural and ecological values of the land trust in the Northern Territory.

Building on long-standing and productive relationships between the Warlpiri, Anmatyerr and Luritja -speaking traditional owners, the CLC and AWC, this new collaboration – the Ngalurrtju partnership – will provide exciting opportunities for mutual learning through the sharing of Aboriginal cultural and ecological knowledge, conservation land management practices and scientific research methods.

“We look forward to working on our country with the CLC and AWC, to protect our sacred sites and look after all the plants and animals,” said Nigel Andy, from the Karrinyarra traditional owner group.

The land trust features many sites of great cultural and spiritual importance. A major ngapa (water) songline travels right through the middle.

CLC chief executive Les Turner said the agreement between the CLC and AWC would provide for strong protection of these sites and included an employment package of approximately $170,000 per year.

“The package will create employment and training opportunities for the members of four estate groups and their communities,” he said. “All these groups will be represented on the partnership’s steering committee, ensuring the area will be managed in line with the traditional owners’ cultural knowledge and obligations.”

The 323,000 hectare land trust in the Great Sandy Desert bioregion at the edge of the Tanami Desert straddles the transition zone at the junction of three arid zone bioregions. It adjoins AWC’s 262,000-hectare Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary.

Together these two properties will protect almost 600,000-hectares of exceptional conservation value.

Central Australia’s biodiversity is under threat from feral cats and foxes, altered fire regimes, feral camels, cattle, horses and weeds. Tim Allard, the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s CEO, anticipates that the partnership will see these threats controlled and biodiversity restored on a landscape scale.

“AWC is working to extend its innovative Indigenous Partnership model by forming a new partnership with the Ngalurrtju traditional owners and the CLC. Together we will be establishing a template for collaborative conservation in Central Australia.”

The adjacent Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary has been effectively managed for conservation for more than two decades.

At Newhaven, AWC has worked with Luritja and Warlpiri-speaking rangers and native title holders for more than 15 years on conservation programs ranging from biodiversity and targeted threatened species monitoring to active land management programs such as fire management and feral animal control.

Science informs all of AWC’s on-ground conservation actions and an extensive science program will be implemented at Ngalurrtju, including monitoring of threatened and culturally important species and ecosystems.

The partnership will complement and extend the work on Newhaven in collaboration with the CLC’s Warlpiri and Anangu Luritjiku rangers and AWC’s Ngalurrtju and Newhaven Warlpiri rangers.

Recording and mapping threatened and culturally important species and ecosystems and building an inventory of extant plant and animal species will be early priorities. This important process helps to identify threatening processes and informs the development of a culturally-based conservation land management program and ‘healthy country’ planning.

The partnership will help to secure populations of some of Australia’s most threatened species, deliver positive cultural and socio-economic outcomes for traditional owners and provide a best-practice template for collaborative conservation in Central Australia.

Follow links for more information on the Central Land Council’s and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s work.

Enid Gallagher leaned forward over the spinifex and clutched her chest in fear. Suddenly, she wasn’t just showing the three young men from Nyirrpi how to track brush-tailed mulgara, she had become the frightened animal.

The animal in question is a small, threatened marsupial Yapa call jajina.

“Jajina wake at night when the lightning strikes,” she said, and pointed to the burrow beneath the spinifex.

Her teenage students learn the difference between fresh and old kuna (poo) left by the small marsupial, and read the tiny footprints around their burrows.

They listened carefully to their kuyu pungu (master tracker), and filled out their work sheets.

Reading and learning the country (yitaki mani) is part of a workshop by eight senior Yapa knowledge holders, educators, Central Land Council rangers from Yuendumu, Nyirrpi and Willowra and other staff.

The week-long workshop at the Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary, 363 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs, included Nyirrpi high school students so they could road-test new learning materials developed by the Yitaki Mani project working group.

The workshop is part of a new CLC project that aims to find out how senior Yapa knowledge holders pass on a lifetime of learning and caring for country to Yapa who grew up in settlements.

Unlike young people today, kuyu pungu and Warlpiri Ranger Alice Henwood was born out bush, west of Nyirrpi, and learned to live off the land. “I’m one of the last bush ladies,” Ms Henwood said proudly.

Now in her sixties, she learned to track as soon as she could walk and follow her parents and aunties on the hunt.

Ms Henwood’s journey took many years, but she feels a sense of urgency to teach her young colleagues.

“I am worried that when I pass away that knowledge will just disappear. That’s why we have to pass the knowledge to the young rangers now, as well as the young people, so they can pass on to their kids,” she said.

“I am worried that when I pass away that knowledge will just disappear. That’s why we have to pass the knowledge to the young rangers now, as well as the young people, so they can pass on to their kids,” she said.

Warlpiri Ranger Alice Henwood, one of the last people to grow up living off the land.

Yapa and the CLC want to fast-track that learning process so that young rangers have access to yitaki maningjaku – everything you need to know to track.

The project working group developed teaching and learning materials that young people can relate to, but that still foreground Yapa knowledge systems.

Kardiya (non-Aboriginal people) typically trap animals to identify what species live in an area, but this only works if something falls into the trap.

A skilled kuyu pungu, however, can tell you the size, diet, territory and hunting patterns, as well as the speed of travel, age and sex of all the animals, reptiles and insects that left tracks around the trap overnight.

“We teach whitefellas, and we also learn from them too,” said Ms Henwood’s daughter and fellow Warlpiri Ranger Christine Michaels.

“Like with the tablets CLC showed us how to store information about endangered animals.”

Yapa knowledge is not just about identifying the animal, it’s also about the purda nyanyi (sensory awareness) of the expert tracker, which is traditionally stored in their head.

Thanks to funding from the 10 Deserts Project, the Yitaki Mani team is developing tools and resources to maintain and promote this knowledge for generations to come.

“I’m getting a little bit sick now, so I really need to pass my knowledge to the younger rangers and the kids.

I’ve been working for a very long time,” Christine Michaels said. “Today the kids from Nyirrpi were really excited to go tracking for jajina and warrarna (great desert skink) and count the burrows.

I was really happy with that.“If young people want to become a ranger they have to work to know their country, spend time with elders on country, and not go into town drinking,” she said.

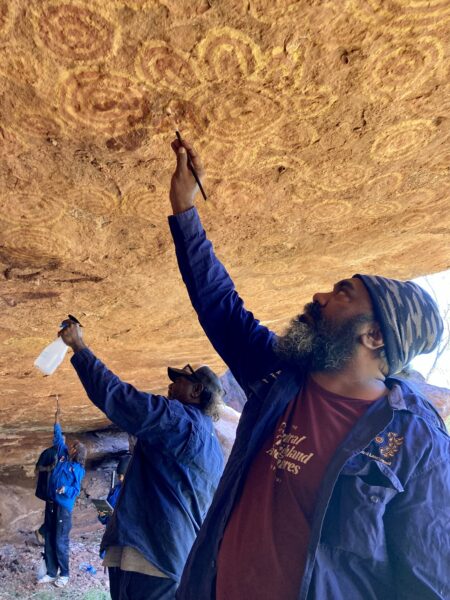

The Ltyentye Apurte Rangers have removed swallow nests from the paintings of their most significant rock art site – with a little help from their friends from Kaltukatjara (Docker River).

Traditional owner Damien Ryder led the convoy of two ranger groups on a trip to Utyetye, a large open cave at the bottom of a cliff on the Santa Theresa Aboriginal Land Trust, to watch them restore the paintings covering the cave roof to their former glory.

He stood at the edge of a cliff that turns into a waterfall after heavy rains, and creates a curtain across the cave opening while topping up the bright green water below.

“The old people used to camp here,” Mr Ryder said, gesturing down into the narrow valley beyond the cave that the rangers have recently cleared of reeds.

Bernard Bell, from Kaltukatjara, clambered down the steep rock face with a cardboard box under his arm, ready to show his colleagues what he learnt at Walka, a cave full of rock art his group is protecting back home.

“I’m teaching them how to look after these paintings and clean off the mud nests,” he said as he inspected the mesmerising design of concentric circles in yellow and orange ochre that covers almost the entire roof of the cave.

Then he pulled a wooden stick and a small hammer out of the box and started to carefully chip away at one of the dozens of mud nests stuck to the ochre.

When only a narrow rim of mud was left he pulled out a spray bottle filled with a clear fluid.

“We spray it with methylated spirits to make the mud soft,” he explained.

The moisture revealed even more paintings underneath the wet mud as he gently swept away the last of it with a soft paint brush.

“We use the brush to clean off the rest of the mud, spray it again, brush again, until it looks nice and clean. It works well. It never takes off the rock painting.”

“It’s been here for a long time and that’s why we need to look after it.”

Farron Gorey, from Ltyentye Apurte, got the hang of it right away.

“It’s a bit different from other ranger work,” he said.

His colleague Anton McMillan already had some practice, having learned the technique during a visit with the Kaltukatjara group.

“My first time was at Docker, where I was doing some training for this kind of work,” he said.

“Nobody has come out here before to clean out the swallow nests to look after all the paintings. It’s part of the history for this country, that’s why it’s important.

“I reckon the traditional owners will be happy with it.”

Mr Gorey agreed.

“I feel good that we can continue to do this, so the old people can see it,” he said.

“I want to bring them here to show them what we have learned. When they see this they are going to feel happy.”

Students in Mutitjulu, Watarrka and Utju are soaking up traditional knowledge at school, thanks to a partnership between Tangentyere Council Land and Learning and the traditional owners of the Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park.

Each school worked with local elders to plan bush excursions and what they wanted to teach on the trips.

Utju studied bush medicine plants, with students learning to prepare rubbing medicine from the witjinti plants they had collected out bush, and drinking and rubbing medicines from ilintji.

The elders’ knowledge, along with the students’ drawings and photos of the excursions, were then used to create teaching resources in Pitjantjatjara and English.

At Utju, they made two language books, Irmangka – Irmangka Palyantja, about making rubbing medicine from eremophilas, and Punti, Muur-muurpa, Witjinti munu Ilintji, Utjuku miritjina irititja kuwaritja, about how to use senna, bloodwood, corkwood and native lemongrass.

“It was a good story and the pictures too. Palya, it’s colourful and a good story,” assistant teacher Rachel Tjukintja said.

Teacher-linguist Leanne Goldsworthy agreed. “The book is beautiful and informative. It’s a great resource to have and a record of knowledge so it won’t be lost,” she said.

Anangu elders, the CLC’s Tjakura Rangers and the national park rangers took Mutitjulu students to Kata Tjuta to harvest urtjanpa (spearwood). They cut mulga wood for wana (digging sticks) and clap sticks from the surrounding woodlands and collected kiti (resin) from the mulga leaves.

They also made kulata (spears) and dug for maku (witchetty grubs). Back at the school, the elders showed the students how to finish their punu (wooden tools) and prepare kiti. They helped the students to record on worksheets what they had learnt. “We make kulata, wanaand music sticks. It was fun, I liked it,” student Sarah Lee Swan said. “The ladies teach us how to make them from the tree with different tools. I want to go camping next time.” Student Nazeeria Roesch agreed. “Yeah, fun. I make stick. I look for maku. Yes, let’s go again,” she said.

Maruku Arts provided the tools for this pununguru palyantja (making tools from trees) trip. With some planned trips cancelled due to COVID-19, Watarrka students illustrated Yaaltji ngiyarilu tjilka mantjinu (How the thorny devil got his spikes), a story told by Brian Clyne and translated by Julie Clyne.

Mutitjulu elders are today launching a new Central Land Council ranger group to manage the vast Katiti Petermann Indigenous Protected Area surrounding the Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park.

Central Land Council chair Francis Kelly says Mutitjulu’s Tjakura rangers – the CLC’s 12th ranger group – are taking their name from the Pitjantjatjara/Yangkunytjatjara word for the threatened great desert skink.

“They are proud to wear the logo with the tjakura on their uniforms because that’s what our rangers are so good at: looking after endangered plants and animals the proper way, under the guidance of their elders.

They don’t just keep country healthy, they also keep people’s culture and knowledge of country strong,” Mr Kelly says.

The Tjakura rangers’ logo is based on a concept design by senior Mutitjulu artist Malya Teamay, who will unveil it at the launch, following a ceremony at 10.30 at the community’s ranger office.

The new group will share the protection of the five million hectare IPA with the CLC’s Kaltukatjara rangers from the remote border community of Docker River, a rough three hour drive west of Mutitjulu.

“I’m so happy my team of six will finally be joined by seven new colleagues from Muti,” said Kaltukatjara ranger co-ordinator Benji Kenny.

“We really needed these reinforcements because it’s been a daunting job to look after an IPA of more than 50,000 square kilometres, an area larger than Denmark or Switzerland, on our own.

“By comparison, the Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park inside the IPA covers only just over 1,300 square kilometres and employs more than a dozen non-Aboriginal rangers, plus another dozen non-ranger staff.”

The IPA is an international hot spot for mammal extinctions, with 18 mammals vanishing from the area since European settlement.

Anangu [pronounced AR-nangu] traditional owners still remember animals such as kantilypa (pig-footed bandicoot), tawalpa (crescent nail-tailed wallaby), lesser bilby, and walilya (desert bandicoot) which died out during the lives of today’s elders.

Feral cats and foxes and changes in traditional fire regimes after Anangu were moved into settlements drive these extinctions.

The Tjakura rangers will help to look after more than 22 surviving native mammal species, 88 reptile species and 147 bird species found on the IPA, including threatened species such as the murtja (brush-tailed mulgara), waru (black-footed rock-wallaby) and the princess parrot.

“We use traditional knowledge and skills such as cat tracking and cool season patch burning and combine them with modern tools such as aerial incendiary machines and digital tracking apps to manage these treats,” Mr Kenny said.

“Having two ranger groups look after the IPA means that we’ll be able to double our efforts and involve more community members on a casual basis, for example to hire more locals to do controlled burns during the upcoming fire season.”

Unique to Australia, IPAs are areas of Aboriginal land traditional owners voluntarily declare and manage as part of Australia’s National Reserve System funded by the federal environment department.

The federal government’s IPA and Working on Country programs provide scarce opportunities for ongoing paid employment for Aboriginal people in remote communities and are highly sought after.

The skills CLC rangers gain through structured accredited training boost their employment prospects in other sectors as well as improve their mental health and wellbeing.

The federal government has delivered on the promise to fund the group, which Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion made in 2015, shortly after Anangu traditional owners declared the country around Uluru Australia’s 70th IPA.